Yellow catches the eye. That's why it's the color of taxis, school buses, road signs, road lines, McDonald's arches, NFL penalty flags, blinking caution lights, Cheerios boxes and the trademarked border of National Geographic. It's also a color of deception, happiness, jaundice and—this year, for the first time ever—both teams in the Super Bowl.

It has roots in nature and epic poetry. Yellow was first mentioned in English a thousand years ago in Beowulf, to refer to a shield made of yellow linden wood—what we would call basswood. From that heroic start, it tumbled into the realm of flawed mortals. It became a synonym for cowards; in the Middle Ages the French painted the doors of traitors' houses yellow. Slanted, sensationalized journalism became known as yellow journalism, a term coined in the late 1890s to describe the circulation-boosting tactics of two rival New York newspapers, both of which ran a comic strip featuring a popular character called the Yellow Kid. "Yellow Kid Journalism" dropped the "Kid" and left us with a term that still applies to certain news outlets today.

Yellow is relatively rare in the sports world, but the Pittsburgh Steelers use it (in combination with black) and so do the Green Bay Packers (in combination with green). The Packers actually wore navy blue and gold (the colors of team founder Curly Lambeau's alma mater, Notre Dame) before switching to green and "taxicab gold"—i.e., yellow—around 1950. Good call: Yellow is a nice aged-cheddar hue for fans who call themselves Cheeseheads.

The Steelers have occasionally used this yellow helmet instead of their usual black one; of the three stars of color in the logo, yellow represents coal, orange represents iron ore and blue represents steel scrap.

Yellows in nature can trick the eye. The sun, seen from space, is a bright white star. We see it as yellow for the same reason we see the sky as blue: Our atmosphere scatters the blue component of sunlight. We're left with light that's more yellow, from the middle of spectrum. (Traditional light bulbs also give light from this yellow range.)

What about yellow objects like bananas, egg yolks and autumn leaves? I learned about this a few years ago when writing a magazine travel article about fall foliage (http://www.viamagazine.com/destinations/ports-fall). The yellow comes from a natural pigment called xanthophyll. It is not as strong a color pigment as green chlorophyll. When green bananas or green birch leaves turn yellow, what's happening is that—as part of the process of ripening, or of seasonal change—the chlorophyll is breaking down and disappearing, allowing the yellow color to show through.

Fall maple leaves along Ocean Drive in Acadia National Park

All of which brings us back to a yellow we immediately associate with nature: The border that rims the cover of National Geographic. Exactly 123 years ago this week, a group of 33 men from various professions—all of them interested in expanding our scientific and geographical knowledge—met in Washington, D.C., and founded the National Geographic Society. No organization has done more to promote scientific exploration, nature photography and public awareness of the natural world. Far from yellow journalism, the work displayed in the society's magazine made Nat Geo (as it now likes to call itself) a pioneer in photojournalism and has earned it more than 20 National Magazine Awards. The yellow cover border is now so familiar that it can stand alone as a logo.

One of the many fascinating details in the history of the National Geographic Society is the role of Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone. Bell, his father-in-law and his son-in-law were all presidents of the society. The son-in-law, Gilbert H. Grosvenor, edited National Geographic for 55 years, and his son and grandson later held that position. Bell himself wrote for the magazine, but under a pen name: H.A. Largelamb, an anagram of A. Graham Bell.

I'd love to hear from any of you who has a favorite image of yellow—in nature, painting, literature, your kitchen cupboard, whatever. I'd also like to hear whether any of you can come up with as good a pen name as Bell by rearranging the letters in your own name. I shuffled mine around and transformed Craig Neff into C.F. Finrage (potentially useful when writing caustic H.L. Mencken pieces), A.C. Fernfig (perfect for authoring botanical treatises) and Nic Gaffer (for my gritty crime novels).

Math becomes a challenge when rearranging Pamelia Markwood into a pseudonym. The number of possible combinations when you're working with 15 letters is more than 1.3 trillion. (You figure that out by multiplying 15 times 14 times 13...etc. all the way down to one—a calculation that mathematicians would call 15 factorial.) Nevertheless, Pamelia could go by A. Wormkip Alamode, Mama Pie Workload, Mope Walk Diorama, Dr. Koala Ammowipe, O. Pami Meadowlark or Pia Makemaw Drool.

If you want to cheat a little in rearranging your name letters, go to a website that will do it for you: http://freespace.virgin.net/martin.mamo/fanagram.html And for what it's worth, if your name were Yellow, you could go by the anagram Lye Owl.

Today's Quiz Match the animals on the right with the collective noun used for a group of those animals (such a flock of geese or a herd of cattle). The answer will be in the next post.

1) Herd..................a) Mudhens

2) Mob...................b) Eagles

3) Convocation.......c) Seagulls

4) Fleet...................d) Kangaroos

5) Squabble............e) Elephants

This is a coot—or mudhen—we saw at the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge in California on our fall bird adventure. What would you call a whole bunch of them?

Birthdays

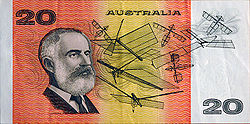

Lawrence Hargrave, the English-born aviation pioneer and inventor of the box kite, would have been 161 years old today. Fascinated by the flight of birds, he vowed to "follow in the footsteps of nature." He did most of his work in Australia, at a windy site now known for its hang gliding. He wrote frequent letters to the press endorsing Darwin's theory of evolution, and emphatically opposed the use of aircraft for war.

Allen DuMont, the American scientist and inventor who not only improved the cathode-ray tube to make it practical for use as a television screen but also sold the first commercially viable TVs, created the first television network and provided the first funding for educational broadcasting, would have been 110 today. Having developed science interest as a boy by reading extensively while bedridden with polio, he started a research lab in his garage with $1,000, half of it borrowed, and eventually became known as the father of commercial television.

Ludolph van Ceulen, the German/Dutch mathematician who spent most of his life calculating the value of pi, would have been 461 years old yesterday. A true man of numbers, he had his tombstone engraved with a 35-digit approximation of pi, the constant (roughly 3.14) that tells us the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter.

Giovanni Borelli, the Italian mathematician and physicist who was father of biomechanics (the study of how the theories of physics and mechanics apply to the body), would have been a spry 403 yesterday. He was the first to declare that muscles only contract. Some of his scientific discoveries did not entirely please religious leaders of the time, but he was protected from the Inquisition through his friendship with a former Swedish queen.

Happy Spring Note?

The Naturalist's Notebook's Nova Scotia correspondent reports that this week she saw geese flying north.