I couldn't stop watching news coverage of Friday's deadly earthquake in Japan. One reason was that I have a friend who lives in Sendai (and whose status I haven't yet been able to determine). But in any such natural catastrophe, the planet's natural forces make compelling television. Seeing those forces in action is the only way to fully grasp their magnitude.

This may seem startling, but the explanation of why and how earthquakes happen wasn't spelled out in a fully, widely accepted scientific theory until the 1960s. Thanks to that theory of plate tectonics, we're now able to understand how the massive rock plates of the Earth's crust move and collide. They travel slowly across the hot, semi-molten mantle beneath them and grind into adjacent plates, uplifting mountain ranges and causing earthquakes and in some cases volcanoes.

Months or years from now, we will see artwork inspired by the Japanese disaster. Not just monuments, but paintings, drawings, songs, novels and poetry to help all of us comprehend the destruction and the enormous loss of life. I came upon an unusual example of earthquake art this morning. In 1968, around the same time plate tectonics were coming into focus, a temblor in Sicily destroyed the mountain town of Gibellina. The town was never rebuilt. Instead, a wildly creative new version of it—designed by modern artists and architects as a statement against political corruption, bureaucracy and the Mafia, and meant to play off the rugged natural environment—rose about 15 miles away. It is, say some who have visited it, a bizarre and eerie place, filled with metal sculptures and a haphazard feel. The new design did not attract many tourists or establish the town as a vibrant creative center. I still find it interesting, however—it sounds almost like the jumbled product of a human creative earthquake. It is a monument of a unique type. And it can be no more strange than the original Gibellina, which was turned into a different sort of artwork by Alberto Burri.

Part of new Gibellina, created by artists after the earthquake.

Burri (who, coincidentally, was born 96 years ago today) buried a large section of the ruins of the original Gibellina in waist-deep concrete in the 1980s to turn it into a piece of "land art." He made pathways where streets once lay. Visitors can thus walk through the city and ponder not just the impact of an earthquake but also deeper questions about the destructive powers of nature and humankind. At The Naturalist's Notebook we're always trying to highlight and merge nature, science and art, and Burri is an example of the creativity that can be spawned by that combination. He was a medical doctor as well as an abstract painter and sculptor. He took up painting while interned in a prisoner-of-war camp in Texas during World War II.

The earthquake-destroyed town after Alberto Burri covered it with concrete and turned it into an artwork.

Ready for Pi (π) Day?

This Monday is Pi Day, an unofficial but semi-widely celebrated brainiac holiday honoring the world's most famous mathematical constant. Don't think of the date as 3/14 but as 3.14, the (rounded-off) value produced by dividing a circle's circumference by its diameter.

If you have trouble remembering that ratio, this might help: Pi—the Greek letter for P—is an abbreviation for P/D, or "perimeter/diameter." O.K., so that's the P. How do you remember the D? Well, good pie is to die for, no? Think Pie/Die.

Pi Day is celebrated at a number of schools and museums, such as the Exploratorium in San Francisco, which has been holding 3.14 festivities for more than 20 years. The slicing of a celebratory cake (a round one, of course) can be used as a math exercise. For example, if you cut a 10-inch-diameter cake into eight equal slices, how wide will each slice be at the frosting end?

Over the course of history, some mathematicians have devoted years to calculating pi to as many digits as possible. It can be a lifetime pursuit; those digits go on indefinitely. Computers have now calculated the constant's value to more than a trillion decimal places.

Besides being essential to geometry, pi has what music executives would call crossover appeal. That is, even non-geeks find it fascinating. Kate Bush, the English singer-songwriter, sang the digits on her 2005 song Pi:

Before Bush's song came along, some people composed "piems" to try to memorize pi's value. Piems are poems in which the number of letters in each word matches a digit in pi. For example, here is piem by Sir James Jeans, the late British physicist, astronomer and mathematician who is credited with inventing this memorization method: "How I want a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics." Count the letters in each word and you get 314159265358979.

Those of you who live in the South may have heard the Georgia Tech sports cheer that makes use of π in playing up the school's science/engineering bent:

"E to the X dy dx,

E to the X dx,

Tangent secant cosine sine,

3.14159,

Square roots, cube roots, Poisson brackets,

Disintegrate 'em Yellow Jackets!"

Given that pi's value is often rounded up to 3.1416, you might want to plan ahead and circle Pi Day on your calendar for 2016, when the celebrations for 3.14.16—a date that comes around only once every thousand years—might rock Times Square. Or, more appropriately, Columbus Circle.

Answer to Last Puzzler:

Maple sap

Today's Puzzler:

Might as well stick with a question I asked above. The perimeter (or circumference) of a circle is pi multiplied by the diameter. If you cut a 10-inch-diameter birthday cake into eight equal pieces, how wide will each slice be at the frosting end?

Birthdays

Albert Einstein would have been 132 years old on Sunday. Perhaps you've heard of him. If you expect me to explain the theory of relativity here in two sentences, well, read the poster below.

Douglas Adams, the English author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and many other books, would have been 59 on Friday. A humorist who contributed to Monty Python's Flying Circus as a writer and (in one episode) an actor, and an environmental activist whose book Last Chance to See, co-written with zoologist Mark Carwardine, focused on endangered species, Adams was a multitalented creative force who worked in every medium he could, from music to radio to video games. His premise for The Hitchhiker's Guide was that Earth was being destroyed by aliens to make way for an intergallactic highway. "There no point in acting all surprised about it," the alien spokesman tells the Earthlings. "All the planning charts and demolition orders have been on display in your local planning department in Alpha Centauri for fifty of your Earth years...What do you mean, you've never been to Alpha Centauri? For heaven's sake, mankind, it's only four light years away, you know."

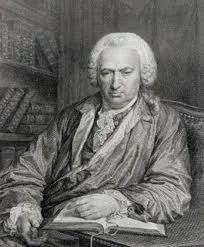

Charles Bonnet, the Swiss naturalist for whom Charles Bonnet Syndrome is named, would have been 291 today. The syndrome, which Bonnet first identified in 1769 in his grandfather, causes a person with vision loss to have vivid, complex hallucinations that can last all day and cause the sufferer to worry that he is developing mental illness. Bonnet contributed to scientific knowledge in other areas as well. Through research on aphids (plant lice) he discovered that some animals and plants reproduce without fertilization by a male. This concept is called parthenogenesis.

Relatively Humorous

If I'm playing up Pi Day, I might as well close with some Einstein jokes.

Q. How did Albert come up with his famous theory?

A. He thought to himself, "If I vere to put my hand on a hot stove for a minute, it vould seem like an hour. But if I vere to sit with a pretty girl for an hour, it vould seem like a minute. By Jove, I think time is relative!"

Q. What was Einstein's favorite limerick?

A. There was an old lady called Wright who could travel much faster than light. She departed one day in a relative way and returned on the previous night.