When Pamelia sees swarms of people, she often says, "We're just ants." She doesn't mean just in a bad way—at least not in reference to the ants. She's just pointing out another of the many similarities between us and other species. In fact, she finds ants amazing, as do I. The above video, passed along by Notebook correspondent Betsy Loredo, offers an unusual look inside an ant colony. The structure—perhaps resembling something we'll build for ourselves on Mars someday—includes farming chambers (ants cultivate fungus to eat), trash depositories, a ventilation system, efficient roadways and, relatively speaking, more space than your typical condo complex. And don't worry as you watch the opening scenes: The colony was abandoned by the ants before the concrete was poured in.

Riding the Ice

A few of the seals who showed up yesterday—right on schedule.

When we looked out yesterday morning, we saw hundreds of common eiders gathered on the bay and at least 17 seals who were sunning themselves on floating chunks of ice. Those sights have become rites of (almost) spring around here. I checked my nature notes from recent years and found this entry from exactly two years ago yesterday: "Lots of eiders suddenly on the bay on a sunny morning—and at least 10 seals sunning themselves on ice blocks floating fairly close to shore."

Forty or more seals live directly across the bay, so we'll be seeing them from now until the fall. The common eiders—large, beautiful, black-and-white ducks—are temporary visitors. They fly to the Arctic to breed, but gather in front of our house in vast numbers before heading north. Several years ago we had a few thousand of them. In the last few years that number has dwindled to a few hundred, causing us to worry that the shellfish draggers who scrape the bay (and wipe out swaths of life on its floor) have been diminishing the food supply the eiders need. We'll see how many more eiders appear over the next week.

Are any migratory birds showing up yet where you live? Please let me know.

Charles Darwin's Earthquake

There's no shame in being beaten to the punch by John McPhee. Drawing upon Pamelia and my voyage around Cape Horn several years ago, a trip that took us through the Beagle Channel and followed part of Charles Darwin's route toward the Galapagos Islands, I'd planned to write this morning about the massive earthquake Darwin experienced in Chile in 1835. I intended to point out how that two-minute temblor, an 8.1 that struck as he was resting under a tree near the Pacific Ocean shore, helped form his view of the Earth and the forces that shape it.

Then I saw that McPhee, the eminent writer and natural-history observer, had pointed out exactly that in a blog post for The New Yorker done one year ago, in the aftermath of an 8.8 quake in Chile. Here is McPhee's post: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/backissues/2010/03/darwin-and-the-chilean-earthquake.html

Given the ever more grim news from Japan, I will instead offer Darwin's own description, in a letter to his sister, Caroline, of the devastation he saw after the 1835 quake:

"I suppose it certainly is the worst ever experienced in Chili (sic). It is no use attempting to describe the ruins—it is the most awful spectacle I ever beheld. The town of Concepcion is now nothing more than piles and lines of bricks, tiles and timbers—it is absolutely true there is not one house left habitable; some little hovels built of sticks and reeds in the outskirts of the town have not been shaken down and these now are hired by the richest people. The force of the shock must have been immense, the ground is traversed by rents, the solid rocks are shivered, solid buttresses 6-10 feet thick are broken into fragments like so much biscuit. How fortunate it happened at the time of day when many are out of their houses and all active: if the town had been over thrown in the night, very few would have escaped to tell the tale."

(Notebook contributor Dr. James Payne sends along this link to Charity Navigator for any of you looking to donate money to help victims in Japan: http://www.charitynavigator.org/index.cfm?bay=content.view&cpid=1221)

Answer to Last Puzzler:

A 10-inch cake has a perimeter (circumference) of 10 times pi (3.14), or 31.4 inches. If you cut the cake into eight equal pieces, each slice will be 3.92 inches wide at the thick end.

Today's Puzzler:

Unscramble each of these into a common word for something you find in nature:

1) aappay

2) leiroo

3) hursth

4) legae

5) mosrw

6) glinngith

Birthdays:

Caroline Herschel, the first woman astronomer, would have turned 261 years old on Wednesday. Limited in her growth by a childhood case of typhus (as an adult she stood 4'3") and trained by her parents to be a house servant, she was drawn to star-gazing as strongly as her more famous astronomer brother, William Herschel. More adept than William at caring for and handling telescopes and and at keeping track of his observations, she became her brother's invaluable assistant and, in her own sky searches, discovered a number of comets.

Coincidentally, William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus 230 years ago this week. He wanted to name it Georgium or the Georgian Planet after Britain's King George III (yes, the same king the American colonists fought against in the Revolutionary War). The astronomical community overruled him, and so the planet was named after the Greek god of the sky.

Norbert Rillieux, the New Orleans-born inventor who revolutionized sugar refining by creating a more efficient evaporation method, would have turned 205 on Friday. A cousin of the French painter Edgar Degas and the son of a white plantation owner and a free African-American woman, Rillieux was a gifted engineer. After sweetening life for sugar companies with his "multiple-effect evaporator," he tried to help New Orleans fight a yellow-fever outbreak by designing a plan for eliminating breeding grounds for disease-spreading mosquitos.

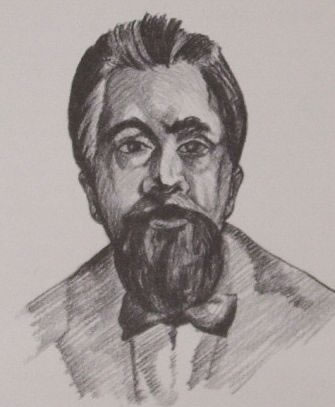

Martinus Beijerinck, the Dutch microbiologist and botanist who first used the the word virus to describe tiny pathogens, would have been 160 yesterday. He found the pathogens on tobacco plants and called them a virus because that is a Latin word for something poisonous or noxious.

Ebenezer Elliott, the British naturalist poet known as the Corn Law Rhymer, would have been 230 on Wednesday. Labeled a dunce as a child, and plagued throughout his life by medical problems that followed a boyhood case of smallpox, Elliott often skipped school to roam the woods and study plant and animal life. He took up botany and plant collecting. At 16 he was sent to work for seven years with no pay in his father's factory, but also began writing poetry. His nickname comes from his opposition to the tariffs (the Corn Laws) set up by Britain to protect its grain industry. A spokesman for ordinary people, Elliott blamed the tariffs for some of his family's financial setbacks. A sampling from The Corn Law Rhymes:

Yes, ye green Hills, that to my soul restore

The verdure which in happier days it wore!

And thou, glad stream, in whose deep waters lav'd

Fathers, whose children were not then enslav'd!

And later...

Dear Sugar, dear Tea, and dear Corn

Conspired with dear Representation,

To laugh worth and honour to scorn,

And beggar the whole British nation.

Let us bribe the dear sharks, said dear Tea;

Bribe, bribe, said dear Representation;

Then buy with their own the dear humbugg'd and be

The bulwarks of Tory dictation.