The Notebook is rolling–or maybe I should say buzzing, like the bees in Julie's drawing above. On Friday, June 24, from 4 to 7 p.m. we'll be holding our season kickoff party and hosting two special guests. Author Judy Paolini and photographer Nance Trueworthy, both of whom live in Maine, will be on hand to sign their book The Inspired Garden: Twenty-Four Artists Share Their Vision. The Notebook tossed a few questions at Judy and Nance about the book:

Q: What sparked the idea?

Judy: Artists often create extraordinary gardens because they use the same elements and principles they use to create their artwork. With attention to form, texture, composition, color, etc, the garden can become a work of art.

Q: What did you hope to convey to readers?

Judy: How these particular artists transfer their knowledge, skills and vision from the studio to the garden. And how the non-artist can utilize their ideas in their own gardens.

Q: How did you go about selecting the artists?

Judy: We looked at the art first. We chose only full-time working artists [from New England]. It was not important that we personally liked the work, although in all cases we did. We reviewed photos of their gardens and visited the local ones to see if they conveyed that same level of skill and vision.

Q: You write about how artists create gardens from an aesthetic perspective rather than a horticultural one and aren't afraid to break the rules. What did you learn from talking to the artists and seeing their gardens?

Judy: Artists aren't afraid to experiment with concepts like color combinations, scale and using exotics as annuals.

Q: How avid a gardener are you and how did you get into it?

Judy: Nance Trueworthy got me going with gardening nearly 20 years ago. I am in the process of eliminating as much lawn in my yard as possible, which is quite a task as about half an acre was lawn when we moved here. I concentrate on trees, shrubs and perennials, using annuals in pots only.

Q: Has your book changed your own view of gardens and gardening?

Judy: Absolutely! One of the most significant insights I took from the book is from Kay Ritter, who states, "After a while every gardener realizes that foliage is the backbone." Because I don't plant a lot of annuals, I now look at foliage first because that is what will be the feature in the gardens most of the season. Perennial blooms don't last long and I want to love my gardens all season.

Judy (left), the author of The Inspired Garden, with Nance, the photographer (who's also a gifted maker of nature-inspired pearl and gemstone available at the Notebook).

Q: How long did you work on the book?

Judy: It took five years from proposal to publication. Because New England has a short growing season it took two summers to see all the gardens. We visited most of them together, Nance shooting as I interviewed the artists.

Q: Nance, what are the challenges of photographing gardens?

Nance: That would be bright mid-day sunshine and [bad] weather. Rain breaks down the flowers and bright sun blows out details on the plants. The best light to shoot gardens is bright overcast light, which brings out great details.

Q: What gear did you use for the book?

Nance: A Nikon camera and various lenses—18mm to 105mm mostly and close-up adapters for the close shots.

Q: Any interesting experiences while shooting it?

Nance: Yes, a frightful moment when Judy spotted a snake sitting in a small pine tree in a garden we were shooting in New Gloucester, Mass. I freaked out and ran, but she took close up shots with her little camera.

Q: What's your own garden like?

Nance: I am a huge gardener. When I bought my house, there was only grass and a little hosta in the back yard. The first thing I did was hire someone to till the soil and I put in a big English cottage garden full of roses, peonies, iris, blue hydrangea and many other things, including some weeping cherry trees, hanoki pine and other pine trees and boxwood.

Another Book Spotlight:

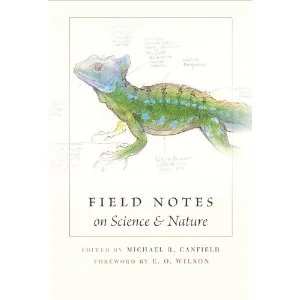

Notebook team member and chief literary critic Eli Mellen has begun writing a series of quick takes on some of the 1,000-plus books we have at The Naturalist's Notebook. The first book he chose is a brand new one that is already a Notebook favorite:

Field Notes on Science & Nature, edited by Michael R. Canfield This book offers a glimpse into the notebooks kept by some of the most influential and respected naturalists and scientists of the last century. Complete with high-resolution reproductions of their notebook pages, this collection will offer any budding naturalist or notebook keeper a lifetime's worth of inspiration.

In his introduction, the eminent biologist and writer E.O. Wilson has this to say, "If there is a heaven, and I am allowed entrance, I will ask for no more than an endless living world to walk through and explore. I will carry with me an inexhaustible supply of notebooks, from which I can send reports back to the more sedentary spirits (mostly molecular and cell biologists). Along the way I would expect to meed kindred spirits, among whom would be the authors of the essays in this book."

Answer to the Last Puzzler:

Which of these are the temporary names given to the two newly discovered chemical elements:

a) unbelievium and underwearium

b) ununquadium and ununhexium

c) unexpectoramus and unforseenium

The answer is b)—ununquestionably.

Today's Puzzler:

The prefix paleo appears in several natural history terms, such as paleolithic and paleontologist.

What does paleo mean?

a) related to dinosaurs

b) lacking sunlight

c) ancient

Birthdays:

British writer George Orwell (Animal Farm) would have been 108 this weekend and painter Robert Henri would have been 146. Henri was part of an American art movement called the Ashcan School, which focused on realistic portrayals of daily life in poor city neighborhoods—a visual cousin of the muckraking journalism of the early 1900s.