If The Naturalist's Notebook had a Mount Rushmore-inspired frieze out front, causing drivers to slow to a crawl as they passed through tiny Seal Harbor, one of the inspiring figures on it would be Leonardo da Vinci, who was born 559 years ago today. Leonardo combined science, nature, art and a curiosity about everything, just as we try to. The difference, of course, is that unlike us, he was a genius.

Leonardo might hold the record for most impressive list of pursuits: painting, sculpting, architecture, music, science, mathematics, engineering, inventing, anatomy, geology, map-making, botany and writing. I might add "notebook-keeping." History's greatest left-hander (sorry, Ben Franklin, Julius Caesar, Sandy Koufax and Kermit the Frog), he filled journals with a prodigious and beautiful output of ideas, words, numbers and sketches. For reasons that have never been known (to prevent others from stealing his scientific ideas? to hide his potentially heretical thoughts on man and nature from the Catholic Church? to avoid staining his sleeve with ink as his left hand went across the page?) wrote right-to-left in reversed lettering that could only be read in a mirror.

One of da Vinci's journals, from about 1505.

His oil-on-poplar-panel Mona Lisa—of a woman from Florence named Lisa del Giocondo, then about 24, in a work commissioned by her husband—may be the most famous painting ever. By contrast, details of da Vinci's personal life are, if you will, sketchy: Vegetarian, never married, possibly/probably gay, religious views uncertain, allegedly so caring about animals that he would buy caged birds just to release them. Generally thought to be a man of high integrity and sensitivity to moral and ethical issues. In the end, of course, his work and ideas speak for themselves.

So who would join Leonardo in The Naturalist's Notebook's Mount Rushmore quartet? First, we would have to expand the group to five people. Five is a Fibonacci number; four isn't. The Fibonacci sequence—which starts 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34...can you guess the next one?—matches numbers found in flowers, pineapples, pine cones and other objects in nature. We like those numbers and the link between math and nature. So five it is.

Off the top of my head, I'll add Charles Darwin, Rachel Carson, Jane Goodall and E.O. Wilson to da Vinci on our Rushmore frieze.

Of these guys, only Teddy Roosevelt (second from right), the greatest conservation figure among U.S. presidents, might have a shot at our Rushmore.

But wait. No Isaac Newton? No Einstein? No Michelangelo? No Galileo? No Pamelia Markwood? Maybe we can do a second frieze out back, hanging above the natural-history deck. Any suggestions for other people we should consider?

Think about that as you go sketch something or write an observation in a naturalist's notebook. And those of you who live in the U.S., remember, don't think of April 15 as Tax Day anymore. Think of it as Da Vinci Day. It's a lot more inspiring.

Animal Caption Contest

The World Wildlife Fund, of which we're happy to be a member, has been running a contest asking people to create a caption for a photo. Below are last month's winner and this month's waiting-to-be-captioned picture:

Book List

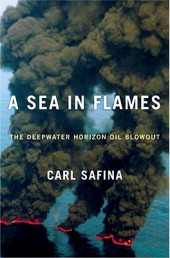

On April 19 one of our favorite environmental writers, Carl Safina (whose fine lecture on commercial fishing, ocean trash and the state of the albatross we attended at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor a few years ago), will release A Sea In Flames: The Deepwater Horizon Blowout. An early review from Publishers Weekly: “Safina’s impassioned account achieves a broad, reasoned perspective that frames events against the more insidious damage that farm and industrial runoff, canal-digging, levee-building, and rising sea level have wrought on the Gulf and its wetlands.”

Safina's organization, the Blue Ocean Institute, has a rating system for buying sustainable seafood that is as valuable as the one published by the Monterey Bay Aquarium. We'll continue to highlight both at The Naturalist's Notebook.

Ever heard someone exuberantly singing opera in the shower? Well, neither have I, but it must sound as happy, loud and rich as the wood thrush now holding court along our dirt road. Other birds are in the chorus too, but I figured I'd share this one song today.

Answer to the Last Puzzler:

All right, so puzzle designer Henry Dudeney went a bit British on us with his 5'10"-man-digging-a-hole puzzle. Here is Dudeney's answer, which makes a distinction between saying you're going "twice as deep" with a hole or "twice as deep again" with a hole:

The man digging the hole said, "I am going twice as deep," not "as deep again." That is to say, he was still going twice as deep as he had gone already, that when finished, the hole would be three times its present depth. Then the answer is that at present the hole is 3 ft. 6 in. deep and the man 2 ft. 4 in. above ground. When completed the hole will be 10 ft. 6 in. deep, and therefore the man will then be 4 ft. 8 in. below the surface, or twice the distance that he is now above ground.

If you figured that one out, we may need to add you to our Mount Rushmore frieze.

Today's Puzzler:

More nature-word jumbles:

a) khars

b) guraja

c) hommsour

d) oomuitsq

e) lawnted

Birthdays:

Hans Sloane, the Scottish-Northern Irish physician who donated a vast collection of books, manuscripts and specimens that helped launch the British Museum and who—more important—may have invented milk chocolate (and chocolate milk?), would have turned 351 on Saturday. He came up with his landmark creation after he tasted chocolate in Jamaica, didn't like it, and decided to see if it was better mixed with milk. Milk and chocolate aren't a bad combo in either solid or liquid form, of course. Earlier chocolate aficionados such as the Aztecs and Mayans had consumed chocolate as a drink, but they had made theirs by grinding cocoa seeds into a paste and adding water, cornmeal, chile peppers, and other ingredients. Both Sloane and a 19th century Swiss chocolatier named Daniel Peter have been credited with inventing milk chocolate, but it seems to me if Sloane lived more than 200 years earlier, he deserves the nod.

Karen Blixen—or, to use her pen name, Isek Dinesen—the Danish author who wrote Out of Africa and Babette's Feast, would have turned 126 on Sunday. Blixen, part of an aristocratic family, married a Swedish baron who was her second cousin and moved with him to Kenya, where they ran a coffee plantation. There she learned about cheating husbands, syphilis, handsome British big-game hunters, accidental shootings and the difficulties of growing coffee in droughts and poor soil, among other things. Meryl Streep played her in the film version of Out of Africa, which won the Best Picture Oscar but was based more on two biographies of her than on the book. The movie version of Babette's Feast won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and gave us a memorable line from Babette, who has just spent all her money to cook a masterpiece of a meal. When she is told that she now faces a life of poverty, she offers a more profound answer: "An artist is never poor."

Vincent (the Wiggler) Wigglesworth, the British insect researcher who found that a growth hormone secreted by the brain controls the amazing process of metamorphosis, would have turned 112 on Sunday. He made that crucial discovery while studying (but not making out with) the South American kissing bug. The Wiggler's memorable name is preserved forever in Latinized label for another of his discoveries, a bacterium that lives in the gut of a tsetse fly. It's called Wigglesworthia glossinidia brevipalpis.

South American kissing bugs